At $1.52 trillion outstanding, student loan debt is now the second largest form of consumer debt in the United States, behind only residential mortgages. This growth has been particularly pronounced among young borrowers. Between 2005 and 2014, average real student loan debt per capita for individuals aged 24 to 32 doubled from $5,000 to $10,000, quickly reshaping the debt profile of American consumers. Unsurprisingly, some have pointed to the increase in student loan debt over the past few decades to explain the decline in homeownership among young adults. During the ten-year period from 2005 to 2014, homeownership in the U.S. fell 4%. Among young adults, this figure was 9%. Given the multitude of negative factors affecting the housing market in the decade after 2005, separating out the effect of student loan debt proves to be a difficult but valuable analysis. In this piece we will attempt to examine the many impacts of student debt on the U.S. housing and structured credit markets, with a focus on potential government interventions to mitigate the negative effects of the debt.

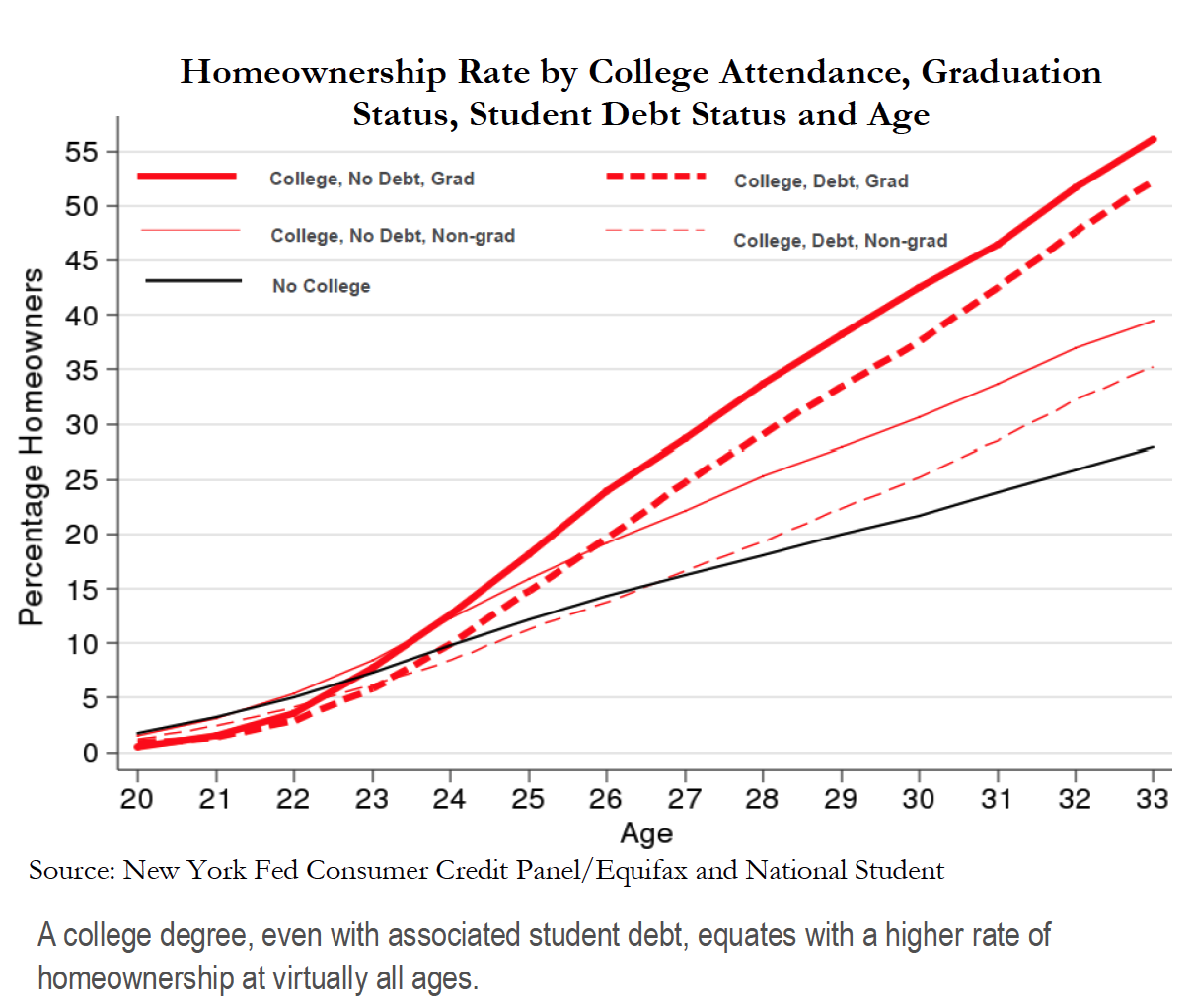

While it may seem somewhat counterintuitive at first, individuals with student loan debt actually have higher homeownership rates than those non-college graduates without any debt. Once past their early twenties, individuals with student loan debt have a higher home ownership rate at every point in their lives than those who never attended college. This is because, by and large, college still remains a good investment. A typical college graduate will earn $500,000 more over their lifetime on a present value basis than a typical high school graduate.1 Compared to the average $30,000 borrowed, financing a college education is unlikely to leave a borrower far behind on earnings, and would not, on average, permanently prevent homeownership.

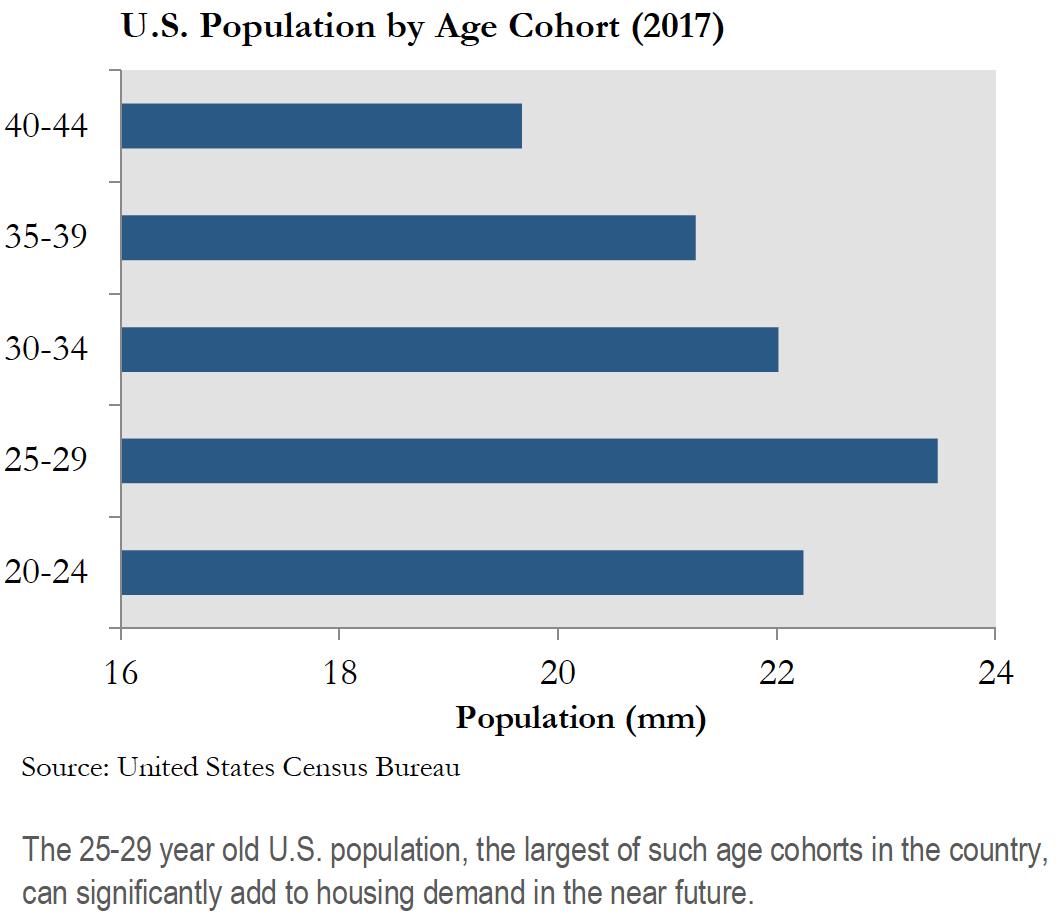

Comparing homeownership rates among college graduates tells a more nuanced story, though. Individuals who borrow for their education lag substantially in homeownership throughout their late twenties and early thirties relative to those who graduate with no debt. In fact, the Federal Reserve estimates that a $1,000 increase in student loan debt causes a 1 to 2 percentage point drop in homeownership rates during the borrower’s late twenties and early thirties. Put differently, over 400,000 young individuals who might have otherwise owned a home in 2014 did not due to incremental increases in student loan debt. Although this figure points towards the conclusion that student loans have seriously dampened housing demand, we believe this decline in homeownership is a timing issue, rather than a structural change to the economy. Instead of preventing individuals from purchasing homes, student loan debt seems to create a lag in demand, pushing first time home purchases later into adulthood. Fortunately for the housing market, population data suggests a significant increase in demand for home buying could be on the horizon. A large portion of millennials will soon move into the 30-34 age group, when homeownership rates tend to increase as student loan debt is paid down.

In addition to delayed homeownership, investors should be aware of the potential geographic repercussions of student loan growth. Individuals with student loan debt are more likely to leave rural areas than non-borrowers, compounding the already present issue of slow job growth and poverty in rural America. In fact, just 52% of rural student loan borrowers still live in rural areas six years after graduating, compared to 66% of non-borrowers. This problem also scales by borrowed amount, with individuals in the highest quartile of student loan debt 41% less likely to remain in rural areas than individuals in the first quartile. As loan amounts grow, so should rural to urban migration. Unfortunately, even without additional debt growth, the economics of the situation show that the migration of educated Americans out of rural communities is unlikely to slow in the immediate future. Typically, borrowers who moved from rural to metropolitan areas in recent years saw an 8.6% decrease in student loan debt one year after graduation, as compared to 3.3% for groups that stayed in rural areas.

A number of states have implemented loan forgiveness programs to counteract urban migration. A few examples include the Idaho Rural Physician Incentive Program (RPIP), the Maine Dental Education Loan Repayment Program, and the West Virginia Medical Student Loan Program. These programs aim to incentivize highly educated professionals to stay in rural areas where lower pay might otherwise extend the life of debt. Although many programs exist, the reality is that few have stemmed the flight of educated Americans to urban centers so far to date.

The Federal government has also enacted legislation aimed at relieving the burden of student loan debt, with very limited success. The Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, enacted in 2007, was meant to encourage careers such as teaching, nursing, and public law. Since inception, 73,000 Americans have applied for assistance through this program, while only 864 have had their student loans forgiven. The Trump administration has recently criticized this program for unfairly rewarding certain Americans at the expense of others and news outlets have suggested the administration may seek to stop the program entirely.

Faced with the potential of increasing student loan defaults, the White House has shifted its focus to the idea of allowing public markets to finance student loans. The administration recently hired McKinsey & Co. to investigate the possibility of selling a portion of the Federal government’s $1.45 trillion student loan debt portfolio to private investors. Under such a plan, the Federal government would maintain its role as the nation’s primary student loan lender, but would shift the long-term risk of the loans onto private investors. Such an arrangement would allow the Federal government to remove the debt off its books in exchange for an upfront payment. However, there seems to be little appetite from private investors to purchase and securitize student loans at levels that make sense for the Federal government. Regardless of the outcome, an unbiased outside assessment of the Federal government’s student loan portfolio could put more pressure on universities to rein in tuition increases.

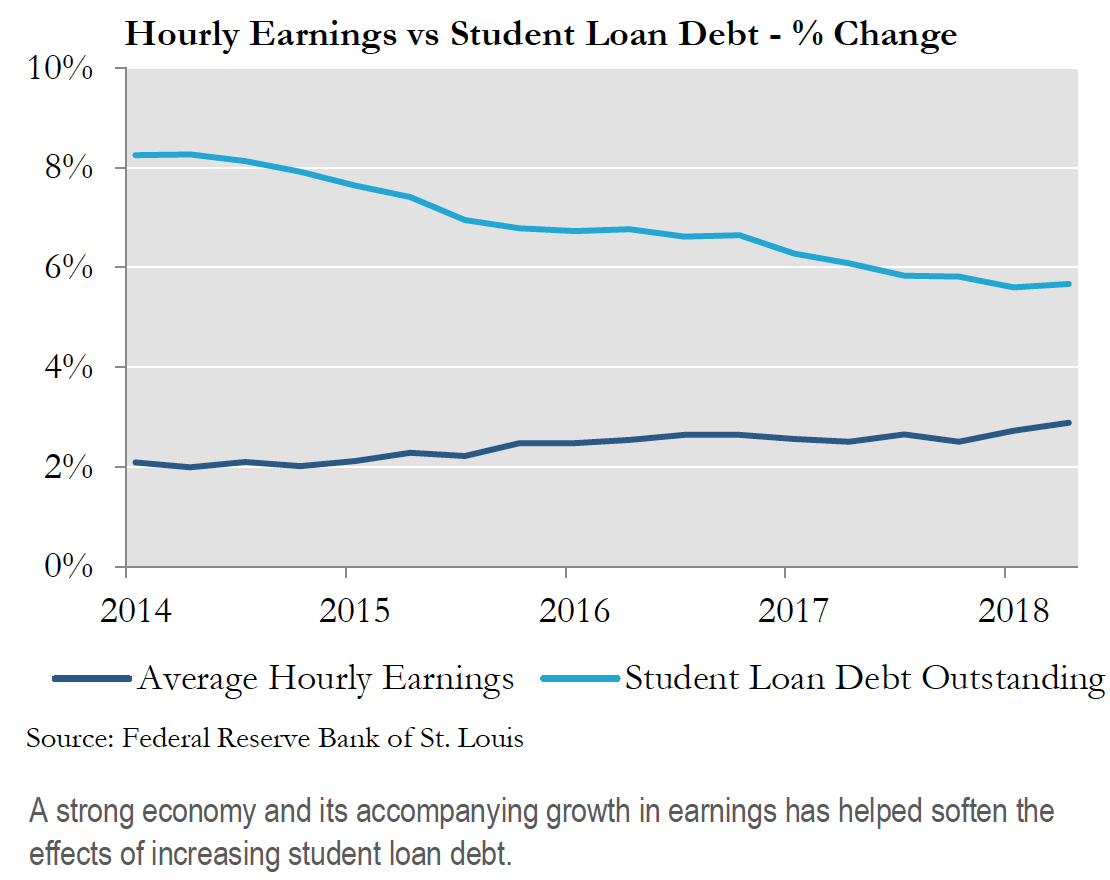

Current trends suggest the effect of student loan debt on the U.S. housing market has been relatively muted. Graduates with debt appear to be entering the housing market on a lag to graduates without debt, but at a similar rate. Population trends also point towards strong future housing demand. Though these trends are positive, they have almost exclusively occurred during a time of extraordinary economic expansion. Average hourly earnings growth has been converging on student loan growth for several years and a strong labor market has prevented high levels of default. The strength of the economy has also allowed legislators to ignore the need for reform. Current state and Federal programs focused on student debt remain underdeveloped, underutilized, and ill-prepared to handle an economic shock and increased default rates. If economic conditions were to turn south, even current debt levels could prove hazardous to homeownership rates, lessening demand from the largest cohort of prospective home buyers. This potential outcome must be closely monitored as we head deeper into the current economic cycle.

Important Notes These materials have been provided for information purposes and reference only and are not intended to be, and must not be, taken as the basis for an investment decision. The contents hereof should not be construed as investment, legal, tax or other advice and you should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax and other matters related to the investments and business described herein.

Investors should carefully consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses of the Ellington Income Opportunities Fund. This and other important information about the Fund are contained in the Prospectus, which can be obtained by contacting your financial advisor, or by calling 1-855-862-6092. The Prospectus should be read carefully before investing. Princeton Fund Advisors, LLC, and Foreside Fund Services, LLC (the fund’s distributor) are not affiliated. Investing involves risk including the possible loss of principal.

The information in these materials does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities from any entities described herein and may not be used or relied upon in evaluating the merits of investing therein.

The information contained herein has been compiled on a preliminary basis as of the dates indicated, and there is no obligation to update the information. The delivery of these materials will under no circumstances create any implication that the information herein has been updated or corrected as of any time subsequent to the date of publication or, as the case may be, the date as of which such information is stated. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and nothing shall be relied upon as a promise or representation as to the future performance of the investments or business described herein.

Some of the information used in preparing these materials may have been obtained from or through public or third-party sources. Ellington assumes no responsibility for independent verification of such information and has relied on such information being complete and accurate in all material respects. To the extent such information includes estimates or forecasts obtained from public or third-party sources, we have assumed that such estimates and forecasts have been reasonably prepared. In addition, certain information used in preparing these materials may include cached or stored information generated and stored by Ellington’s systems at a prior date. In some cases, such information may differ from information that would result were the data re-generated on a subsequent date for the same as-of date. Included analyses may, consequently, differ from those that would be presented if no cached information was used or relied upon.

AN INVESTMENT IN STRATEGIES AND INSTRUMENTS OF THE KIND DESCRIBED HEREIN, INCLUDING INVESTMENT IN COMMODITY INTERESTS, IS SPECULATIVE AND INVOLVES SUBSTANTIAL RISKS, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, RISK OF LOSS.

Example Analyses Example analyses included herein are for illustrative purposes only and are intended to illustrate Ellington’s analytic approach. They are not and should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any financial instrument or class of financial instruments.

Forward-Looking Statements Some of the statements in these materials constitute forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements relate to expectations, beliefs, projections, estimates, future plans and strategies, anticipated events or trends and similar expressions concerning matters that are not historical facts. The forward-looking statements in these materials are subject to inherent qualifications and are based on a number of assumptions. The forward-looking statements in these materials involve risks and uncertainties, including statements as to: (i) general volatility of the securities markets in which we plan to trade; (ii) changes in strategy; (iii) availability, terms, and deployment of capital; (iv) availability of qualified personnel; (v) changes in interest rates, the debt securities markets or the general economy; (vi) increased rates of default and/or decreased recovery rates on our investments; (vii) increased prepayments of the mortgage and other loans underlying our mortgage-backed or other asset-backed securities; (viii) changes in governmental regulations, tax rates, and similar matters; (ix) changes in generally accepted accounting principles by standard-setting bodies; (x) availability of trading opportunities in mortgage-backed, asset-backed, and other securities, (xi) changes in the customer base for our business, (xii) changes in the competitive landscape within our industry and (xiii) the continued availability to the business of the Ellington resources described herein on reasonable terms.

The forward-looking statements are based on our beliefs, assumptions, and expectations, taking into account all information currently available to us. These beliefs, assumptions, and expectations can change as a result of many possible events or factors, not all of which are known to us or are within our control. If a change occurs, the performance of instruments and business discussed herein may vary materially from those expressed, anticipated or contemplated in our forward-looking statements.

PRINCF-20190924-0033